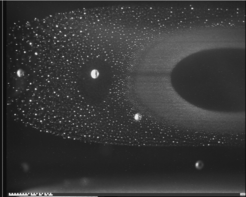

Dramatic end of plasma crystal experiment

This picture was taken during the last experiment with PK-3 Plus on the International Space Station. You can see some "large" particles of about 1 mm in diameter, which were induced into the experiment chamber by accident, but which led to interesting interactions with the smaller particles.

Basic research on plasma crystals (which gave the “PK” experiments their name) or more generally research on complex plasma deals with a new state of matter that was discovered only recently. Originally the researchers studied dusty plasmas, which occur, for example, at the boundary layers between the Earth's atmosphere and interplanetary space. But then the scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics discovered in the 1990s some entirely new effects. Although a plasma (an ionized gas) is the fourth and most disordered state of matter, some order can be achieved/induced by injecting small particles into the plasma. The particles are about one thousandth of a millimetre in size and form structures that exhibit crystalline or liquid properties.

The complex plasma provides a model system that can provide interesting insights and basic information for many areas of physics. Because the particles are relatively large, the scientists are able to watch each individual particle of a crystal lattice in the plasma and track its dynamic. Thus, the researchers gain insight on the most fundamental, i.e. the kinematic level. Phase transitions such as melting and crystallization, or the separation of binary systems can thus be examined in detail.

On Earth, only 2-dimensional or 3-dimensional stressed systems can be studied because of the mass of the particles and their sedimentation in the gravitational field. Experiments under micro-gravity conditions were therefore performed early-on. Complementing its ground-based research, in 2001 a team of Russian and German scientists brought the first plasma crystal laboratory onto the International Space Station, bilaterally funded by Russia and Germany (DLR/BMWi) and built by the German aerospace company Kayser-Threde and the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics. This research was so successful that the successor laboratory, PK-3 Plus, was commissioned immediately. In late 2005, the first experiment PKE-Nefedov was then replaced by the new laboratory on the ISS.

PK-3 Plus, which was again developed, built and operated by the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics and the aerospace company Kayser-Threde, was able to further extend the great success of the first laboratory. With new experiments the scientists could confirm that complex plasma is actually a new state of so-called soft matter, which includes granular materials, colloids in liquid suspensions, and others. This realization opened up a wide range of new scientific issues and points to a long and promising future for this research field.

The technology for producing cold plasma is now also used for medical purposes. In the world's first clinical trial, the participating scientists and doctors were able to demonstrate that the plasma not only kills germs, but shows wound-healing effects as well.

The last experiment with PK-3 Plus was carried out on 14 June 2013 on the ISS - this brought the apparatus to its limits. Cosmonaut Pavel Vinogradov inserted an unprecedented number of particles into the plasma; inadvertently, also some large globules with a diameter of about 1 mm reached the experimental chamber. The interaction of these "huge" particles with the dense clouds of "small" particles was spectacular to see, and provided interesting information as well. To make sure that these globules floated through the complex plasma repeatedly (see figure), the cosmonaut was asked to bump into the container housing the lab again and again. Thus the scientists on Earth received a wealth of new images and data that now have to be evaluated in detail.

A prize for technology transfer from basic research to application: Based on a fundamental physics experiment, the group was awarded the prize for "Top Medical Application" of the ISS – a development that was completely unpredictable.

In addition to the many interesting topics in physics research, an application arose in a completely different area based on the knowledge of the space experiment - a development that could not have been foreseen initially. The technological development to produce a cold plasmas led to devices and applications in the newly emerging field of "Plasma Medicine". This is based on the germ-killing effect of cold atmospheric plasmas (CAP), bacteria , viruses, fungi and spores of any kind are killed after a very short time. Other cells, such as normal skin cells, however, are not affected. In an interdisciplinary collaboration, the group at the MPE studied the effect of CAP on chronic wounds in the first clinical trial worldwide, and was able to demonstrate not only the sterilizing character of the plasma, but also that this treatment boosts/stimulates/supports wound healing (see figure).

For this knowledge transfer from basic research in space to an application on Earth, the group was awarded with a prize at the July conference on science and development on the ISS in Denver by the American Astronautical Society. A great success for the scientific partners from Germany and Russia, and for the participating space agencies DLR and ROSKOSMOS.