A galaxy with a double heart

It is well established by now that almost all massive galaxies host a supermassive black hole at their centre. The black hole at the centre of the Milky Way has a mass of about 4 million times the mass of the Sun, as has been measured by tracking the orbits of stars around the galactic centre (see here). Measuring the mass of supermassive black holes in far-away galaxies is trickier, since astronomers cannot follow the paths of individual stars. However studies of the overall gas kinematics and stellar dynamics at the centre of galaxies have revealed tight correlations between the black hole mass and parameters of the galaxy such as its bulge mass or bulge luminosity, suggesting that the formation and evolution of galaxies and their supermassive black holes are closely linked.

In massive elliptical galaxies, so-called "core-ellipticals", an intriguing mechanism produces extensive diffuse centres. These massive galaxies grow by merging of smaller galaxies; their central black holes spiral into the centre of the merger via dynamical friction, forming a supermassive black hole binary. The stars at the centre are either swallowed by the growing black holes or scattered to larger radii via gravitational slingshot. Eventually, the two black holes will merge to form a single, larger black hole at the centre of the larger galaxy. While this process seems to work well in numerical simulations, direct observational evidence of binary supermassive black holes has been scarce.

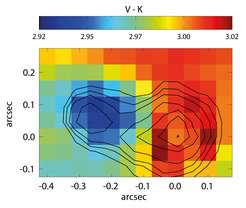

This zoomed image shows the difference in colour (V and K bands) of the central region after the subtraction of the central point source. The contours correspond to the brightness in the HST image. The second nucleus is clearly visible, and is slightly bluer than the rest of the galaxy, indicating a younger stellar population.

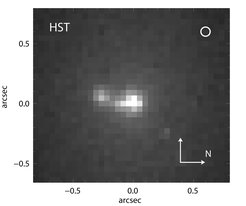

“We observed NGC 5419 together with some 30 other large elliptical galaxies to learn more about the interplay between galaxies and their supermassive black holes,” explains Roberto Saglia, who led the study. “When we saw the double nucleus we were very excited.”

The MPE astronomers obtained high-resolution observations with the adaptive-optics SINFONI instrument at the Very Large Telescope (VLT). As an integral field spectrograph, this produced not only detailed images of the centre, but also provided information about the stellar kinematics. Data from the Southern African Large Telescope (SALT) provided additional velocity measurements for the outer parts of the galaxy.

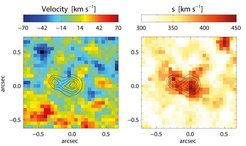

The analysis of the dynamics of the galaxy shows that it harbours a supermassive black hole with a mass of some 7 billion solar masses (2000 times more massive than in our Milky Way). However, the velocity dispersion and the associated mass for the secondary nucleus cannot be accounted for by stars alone. This suggests that there is a second black hole of at least 1 billion solar masses, separated by only 75 parsec (or about 200 lightyears).

These two kinematic maps show the velocity (left) and the velocity dispersion (right) at the centre of galaxy NGC 5419. The velocity dispersion of the galaxy overall is on the order of 350 km/s and reaches higher values in an extended region coincident with the position of the nuclei. Surprisingly, however, the velocity itself is very small at the centre of the galaxy, which most likely means that the orbital motion of the black holes is mainly perpendicular to the line-of-sight.

“Our data not only confirmed the double nucleus in the spatial data, but also in the velocity maps,” summarises Roberto Saglia. “Most likely this galaxy hosts not only one, but two supermassive black holes at a fairly small separation, making this a promising target to study the interaction of black holes at the centre of a galaxy. We plan to obtain additional high-resolution radio data for NGC 5419, which could detect a wobbling jet indicating the orbital motion of the binary black hole.”