"The IMPRS does not have to hide from the doctorate programmes of the American elite universities"

Interview with coordinator Prof. Dr. Werner Becker on the 20th anniversary of the IMPRS on Astrophysics

The International Max Planck Research School (IMPRS) on Astrophysics, in which the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE) plays a leading role, celebrates its 20th birthday in these days. Prof. Dr. Werner Becker, scientist in the Department of High Energy Astrophysics at MPE and coordinator of the IMPRS on Astrophysics since 2001, has been involved from the very beginning. Here he recalls the process of development of the IMPRS, explains the difference in doctoral training between 20 years ago and today, and explains why a Munich dentist once sent a hefty bill to the MPE.

Mr. Becker, the IMPRS on Astrophysics is celebrating its 20th anniversary this year. The actual beginnings, however, date back several years ago. What could you describe as the "big bang" of the IMPRS? What was the basic motivation for its founding?

Among other things, the Max Planck Research Schools were intended to create closer links between Max Planck Institutes and universities. You have to know that the cooperation between many universities and Max Planck Institutes – which are often even at the same location – was not always the best in the past. Lecturers at the universities, who in addition to their research activities also had teaching duties, sometimes looked, not without envy, at their colleagues at the MPIs, who, usually well financed, devoted themselves exclusively to their research activities; and then ended up – without having invested anything in the training of young scientists – being the first port of call for them.

Was this view justified?

Since 2004 I have been giving lectures regularly at the LMU and meanwhile know how time-consuming it is, I can at least very well understand the point of view of many colleagues at the universities. The universities were categorically underfunded for decades. It was therefore a really good idea of the then President Hubert Markl to get involved in doctoral training, and to set up the International Max Planck Research Schools in cooperation with universities. At the same time, through internationalization, you achieve a worldwide visibility of the Schools and the institutes, universities and scientists involved in it.

And you became coordinator for the IMPRS on Astrophysics. How did you get this honor?

I came to MPE in 1990 and about four years later I finished my doctoral thesis on a topic related to neutron star research with the X-ray satellite ROSAT. After that I was in the ROSAT team for a few years, developing software for arrival time analysis of X-ray photons. At the beginning of 1999, the then Managing Director of the Institute, Joachim Trümper, approached me and told me about the MPE's plans to apply to a call for proposals from the Max Planck Society for the foundation of an International Max Planck Research School – together with the neighboring institute MPI for Astrophysics (MPA), the European Southern Observatory (ESO) and the University Observatory of the LMU. If successful, the Society promised start-up funding for this Research School from its budget for an initial period of six years, as well as additional funding for doctoral student positions and the position of a coordinator. The whole thing was to be the start of the International Max Planck Research School on Astrophysics at the Ludwig Maximilian University, following the example of American doctorate schools. And Joachim Trümper asked me if I wanted to get involved.

And you wanted to?

Yes, because an essential aspect was the training of doctoral students, and that fitted in with my general plan to habilitate and obtain the authorization to teach, so that I could pass on my knowledge to young students of astrophysics. But I didn't necessarily expect at the beginning that the lectures would ultimately only make up a small part and that I would instead take over the entire coordination of the IMPRS (laughs).

Good thing that after a few years you were at least supported by an assistant...

That's right. From 2011 on, Veronika Schubert supported me, and since 2017, Annette Hilbert has taken over this task. And, I really have to emphasize at this point, without the great commitment of Ms. Schubert and now Ms. Hilbert, the IMPRS would not function as it does. In addition, the numerous colleagues from the participating institutes who take part in the lectures for the doctoral students and pass on their knowledge make a decisive contribution to the success of the IMPRS – as does Annegret Lorf, who puts her heart and soul into the Research Schools on behalf of the Max Planck Society.

How do you launch a completely new doctorate school?

That requires a lot of improvisation, because in the beginning, of course, there were no blueprints, no website, no texts or even a uniform email address. All that had to be developed first. Since I had never attended a doctorate school myself, I first did some research and looked at the structure and organization of doctoral programmes in the US and UK.

Fortunately, not only one IMPRS was established...

That's right. Of course, it was very helpful that at the same time as our IMPRS on Astrophysics, about a dozen other IMPRS were founded, all of which faced the same problems and challenges. The mutual exchange was extremely helpful, and special thanks must also go to Ms. Nicola von Hammerstein from the Administrative Headquarters of the Max Planck Society, who made a decisive contribution to the success of the IMPRS, especially in the first few years, and was not without reason considered the "mother of the IMPRS" by all the coordinators.

How is the IMPRS on Astrophysics funded?

As with all other IMPRS, the money for our IMPRS comes from the central funds of the Max Planck Society and the budget of the participating institutes. A grant is always valid for six years, and after four years an evaluation is carried out by an external, international committee – similar to the review by the scientific advisory board that the Max Planck Institutes have to undergo every few years. And as with the advisory board, accountability reports must be submitted, and doctoral students also present their research topics and results in lectures and at a poster session.

Where do you see the greatest advantages for doctoral students?

20 years ago, as a doctoral student you were typically a lone fighter. In my time, there were about 30 doctoral students at the Institute, each of whom pursued his or her research topic without much "looking left or right". Apart from that, joint activities or excursions were rarely organized, and there were no joint lectures at the institute either; that all took place at the universities.

And today?

Today, the doctoral students see themselves as a common unit, and as a result they have much more weight as a group at the institutes. As an example, I would refer to the Executive Committee of the IMPRS, which includes representatives of the institutes participating in the IMPRS as well as doctoral students from each year group, who actively support the interests of young researchers.

Another great achievement is the student symposium that takes place twice a year and is organized by the doctoral students themselves. There they learn to give scientific presentations, they get an insight into the work of their fellow students and thus possibly discover new approaches to solving their own challenges. They support each other, generate new synergy effects and, also thanks to regular joint activities such as excursions, parties or visits to the beer garden, create a strong sense of togetherness that binds them together for life – with each other, but also with the institutes. That is the great merit of the IMPRS.

In 20 years as IMPRS coordinator, you probably experience all kinds of curious things. There are certainly many stories to tell, aren't there?

Spontaneously, two stories come to mind: Once, there was a reality show on ProSieben where you could undergo cosmetic surgery, among other things with a dentist or orthodontist from Munich. One of our doctoral students heard about it, obviously saw a need and went to the aforementioned star dentist – firmly believing that the procedure would be paid for by the health insurance.

But that was not the case?

No, there must have been some kind of misunderstanding. In any case, a reminder from the dentist for several thousand euros arrived at our institute at some point. The doctoral student insisted, however, that the costs had to be covered by the health insurance. However, this was the cheapest of all possible private health insurances, which covered practically no costs for anything. I can't say what the final outcome was, because MPE rightly refused to pay the bill. All I know is that the doctoral student eventually left the MPE. I guess the dentist was left with the costs.

And the second anecdote?

It was about a doctoral student. A few weeks after the student started to work with us, a colleague stood in my room and asked what the young researcher was doing that was so time-consuming; the entire power of the central computer had been used for days, so that not even the cursor was moving on his screen. Eventually it turned out that the doctoral student had given access data for the institute's computer to the former thesis supervisor of the student's home country, who was using our computing power from there to carry out complex simulations for his own research. That was crazy (laughs).

Finally, let’s take a look into the future: the new institute building of the MPI for Physics (MPP) is currently being built directly across the MPE, and the move to Garching is planned for the end of 2022. Are there any plans to integrate the MPP into the IMPRS on Astrophysics?

I don't think the MPI for Physics will become a permanent partner of our IMPRS, especially since the institute already has its own doctorate programme with the IMPRS on Elementary Particle Physics and works together with thematically related groups at LMU and TUM. However, it is certainly the case that there has already been close cooperation between the two research schools for many years. For example, doctoral students from the Werner Heisenberg Institute of Physics can attend our lectures, and vice versa. Trips and excursions are also increasingly planned jointly. The future spatial proximity will certainly intensify the cooperation between the institutes, so that the move will generate new synergy effects, from which – I am firmly convinced – everyone involved can only benefit!

What is your conclusion and how do you see the future of the IMPRS? Currently, the IMPRS is funded until 2025.

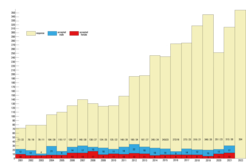

I hope that the Max Planck Society will continue to recognize the benefits of the IMPRS and provide the necessary financial resources. In my opinion, the costs are relatively manageable for the MPG, but the success is extraordinary: 350 doctoral students have completed their doctorates at the IMPRS on Astrophysics so far, many of whom have gone on to very successful scientific careers, some even have reached professorial positions. For the approximately 25 doctoral positions that we award on average, we receive several hundred applications each year. In total, more than 4250 students from 103 countries have applied for a doctoral position so far, which clearly underlines the international character of our IMPRS. And not at least the fact that our concept is now widely adopted by research institutes in other neighboring European countries, shows that with the IMPRS a truly groundbreaking institution has been created – which in no way has to hide from the doctorate programmes of the American elite universities! Quite the contrary: Our IMPRS, with around 100 current doctoral students, is one of the largest graduate schools in the field of astrophysics worldwide.